SOMETIMES IT PAYS OFF TO MAKE A MOUNTAIN OUT OF A MOLEHILL. In the days before slopeside condo developments, hedge funding, and the corporatization of the ski industry, small ski slopes of the 1960s and ‘70s relied on families — moms, pops, and kids who groomed the slopes, ran the rental shops, and cut their own slalom gates from tree branches. Often their hard work and dedication paid off in ways no one could predict… as it did for the Kreiner family of Timmins, Ontario.

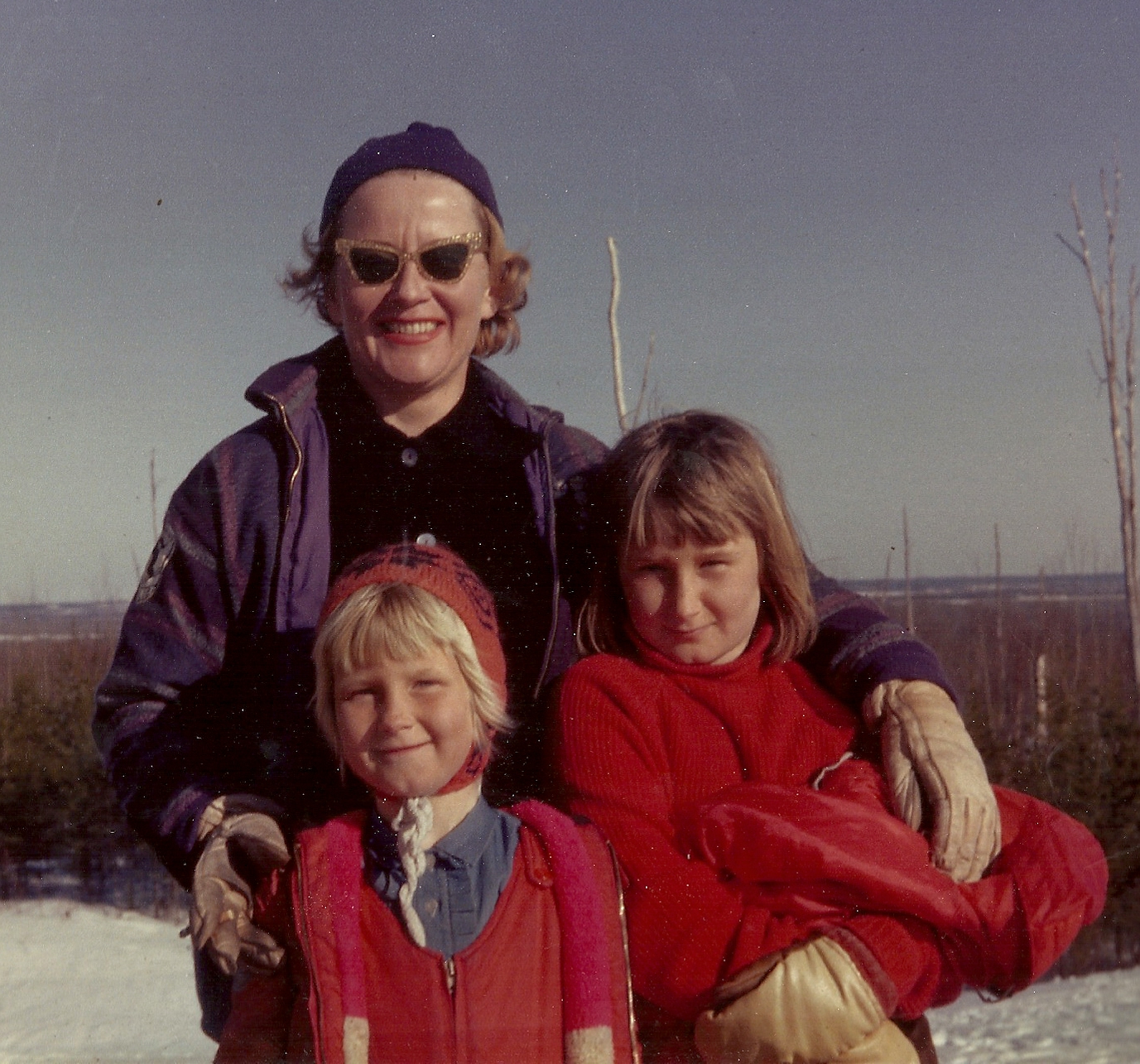

Their family’s ski story starts in the early 1960s with Hal and Peggy Kreiner pouring their hearts and a great deal of soul into the Timmins Ski Club. Much of the family’s discretionary income went into the development of a hill with 400 vertical feet — now Kamiskotia Snow Resort — situated amid the gold, copper, and zinc mines of Northern Ontario.

Hal, a family physician, spent his spare time developing the ski area and running the ski patrol. Peggy made brown bag lunches for her six children: Tom, Libby, Jim, Philip, Laurie, and Kathy. She organised the kids’ hand-me-down ski equipment, fed ski patrollers and ski instructors at her dinner table, and ferried Timmins ski teams across Northern Ontario for alpine races. Their routes took them between Timmins, North Bay, Sault Ste. Marie and beyond in the family station wagon, often in the middle of the night in temperatures so cold the fuel lines would freeze. Says daughter Laurie Kreiner, the family historian: “We discovered a bottle of rye can go a long way in melting a frozen gas line.”

During those years—what Laurie calls “the rudimentary days” of their family ski life—the Kreiners were immersed in the basics of running a ski area: maintaining outhouses, T-bars, and rope-tows, cutting new runs with crews of volunteers… Laurie says: “All this because of our dad’s vision, in his spare time, while also working as a busy family doctor and delivering half the kids of Timmins!”

“We helped him repair and rewind T-bar springs in the basement,” she adds. “We spent every weekend after Labour Day at the hill doing the work needed, along with many, many other volunteers.”

More to the Story

But there’s more to the Kreiner story than the toils of building and operating an all-consuming family ski area. In 1960, Anne Heggteveit’s gold medal at Squaw Valley — Canada’s first Olympic slalom win — may have been the catalyst that caused the unexpected; it pushed the Kreiners onto skiing’s world stage.

First, Laurie Kreiner pasted Heggteveit’s poster to a wall in the family home and vowed to ski in the Olympics one day. Shortly after, her father Hal volunteered as Canada’s National Ski Team doctor, earning the nickname Cool Doc for his easy demeanour and his passion for ski racing.

His letters home from the 1966 World Ski Championships in Portillo, Chile described a world in which Nancy Greene and Jean-Claude Killy reigned as ski racing’s queen and king. Spider Sabich, Bob Beattie, Howard Head, Bob Lange, and David Jacobs of Spyder were on the scene. Laurie Kreiner became even more determined to join them. Her sister Kathy was never far behind.

Laurie made it to the Canadian Championships in Thunder Bay at age 13. By age 14 she and her brother Jim were loaded on a train bound for summer ski camp on BC’s Kokanee Glacier, their younger sister Kathy, 11, in tow.

“We got off the train in Calgary and Kathy’s knapsack was gone,” Laurie remembers. “All her clothing, ski boots, everything was missing. I called my parents from Nelson and they told me to go out and buy her clothes. When we got to the glacier, Nancy Greene lent her a pair of Lange ski boots!”

“The whole Kokanee experience was such a riot,” Laurie adds. She remembers cold nights sleeping in tents and early-morning breakfasts served by a cranky cook who told them to “eat what’s in front of you.” On the glacier they raced through bamboo gates, their speeds clocked, not by sophisticated Longines timing systems, but with hand-held stopwatches. Says Laurie: “At night we stored our skis under the rocks so the marmots couldn’t eat our leather boots and long thongs.”

The trip was a turning point for the Kreiner sisters. “We were very coachable,” Laurie says. “Dad had told us: Never give up. So we didn’t. We were young and considered outsiders but we turned out to be among the fastest.” After the camp, Laurie was invited to join the team for further training; coaches kept eyes on little sister Kathy, who joined the team a few seasons later.

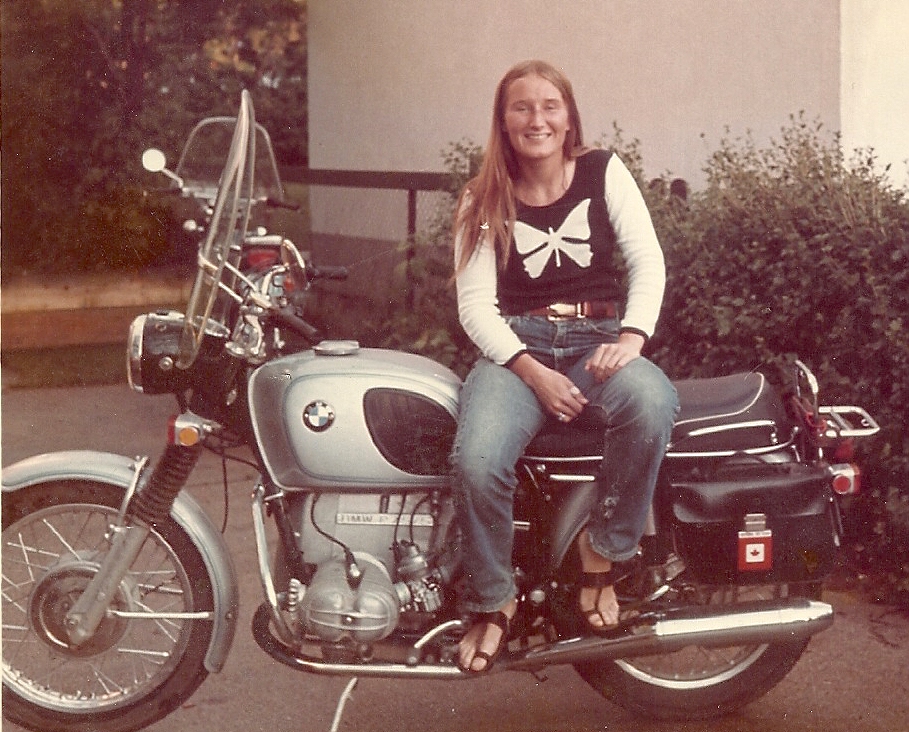

The World’s Ski Stage

From grade 9 forward, Laurie Kreiner was on the road, travelling to ski races alongside Betsy Clifford, Billy Kidd, and Marie-Theres Nadig. “On a flight to the World Cup finals at Squaw Valley, I sat beside Spider Sabich,” she says. “He told me: I always sit in the back ‘cause when a plane crashes the front gets mangled. He was 10 years older than I was, I’m surprised he even spoke to me.”

Laurie’s best Olympic results were in Sapporo, Japan in ’72, where she placed a heartbreaking fourth in the Giant Slalom. “I missed winning a medal by .13 of a second.”

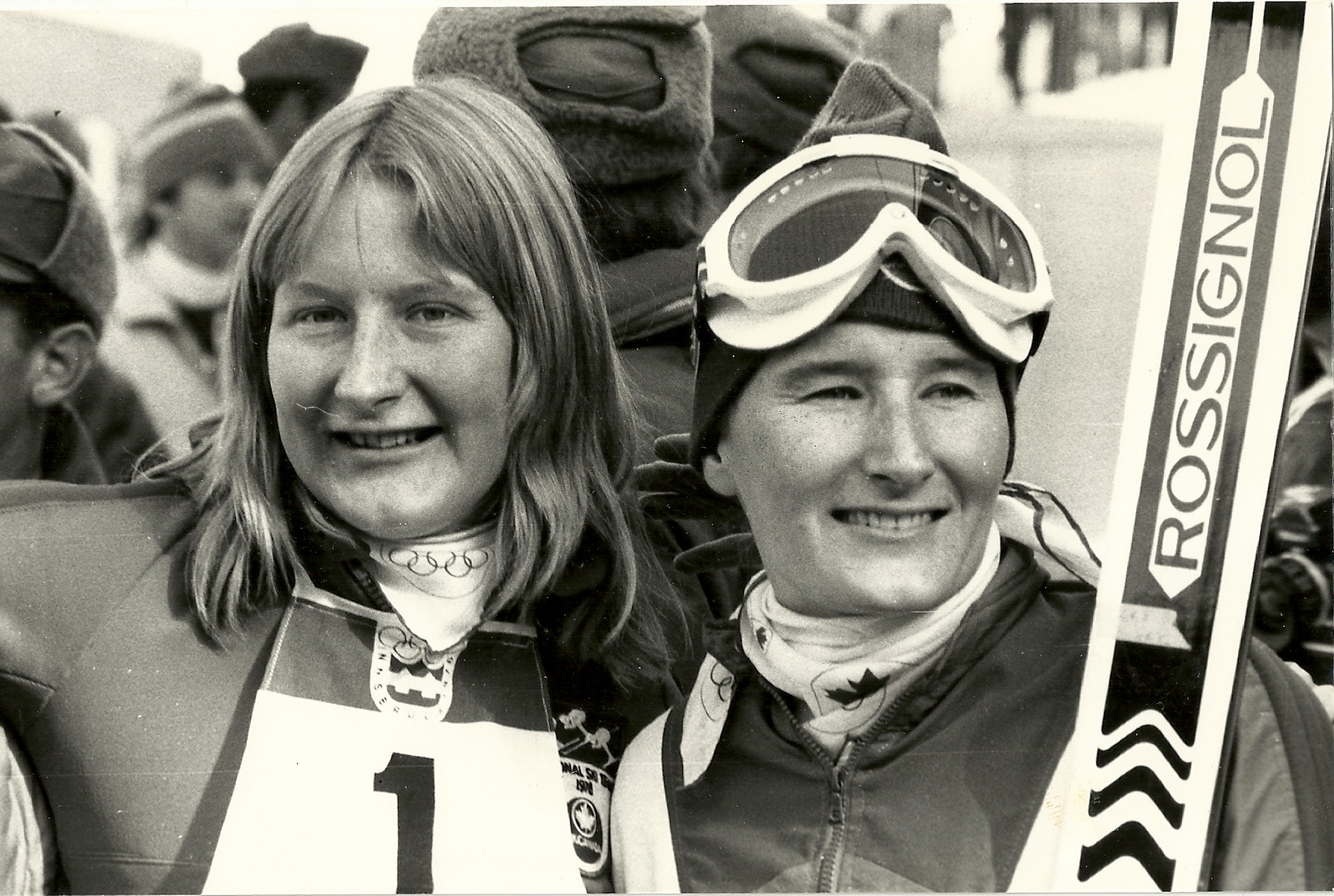

Then, in 1976 at the Olympic Winter Games in Innsbruck, Austria, sister Kathy Kreiner made history.

“The girls hadn’t been having a great year,” Laurie says of Canada’s women’s ski team leading into those memorable ’76 Olympics. “There were only three of us: Betsy, Kathy, and myself. Nobody expected us to do anything because the focus was on the guys, whom the Europeans were calling The Crazy Canucks.”

“Kathy had start No.1,” she continues. “It was a good slope, fairly steep all the way down, the surface was hard and icy. Kathy had a great run but nobody knew how good it was until the end… all the others slid off the course. She was standing down there, at the bottom of the run with no media around her.”

“Jungle Jim Hunter put her on his shoulders when they realised she won — that’s the story behind that famous photograph of Kathy and Jungle Jim. It became a great story for Canada for both the ’76 winter and summer Olympics. No other Canadian won gold.”

Kathy Kreiner was only 17 years old — to that date, the youngest skier to win a gold medal.

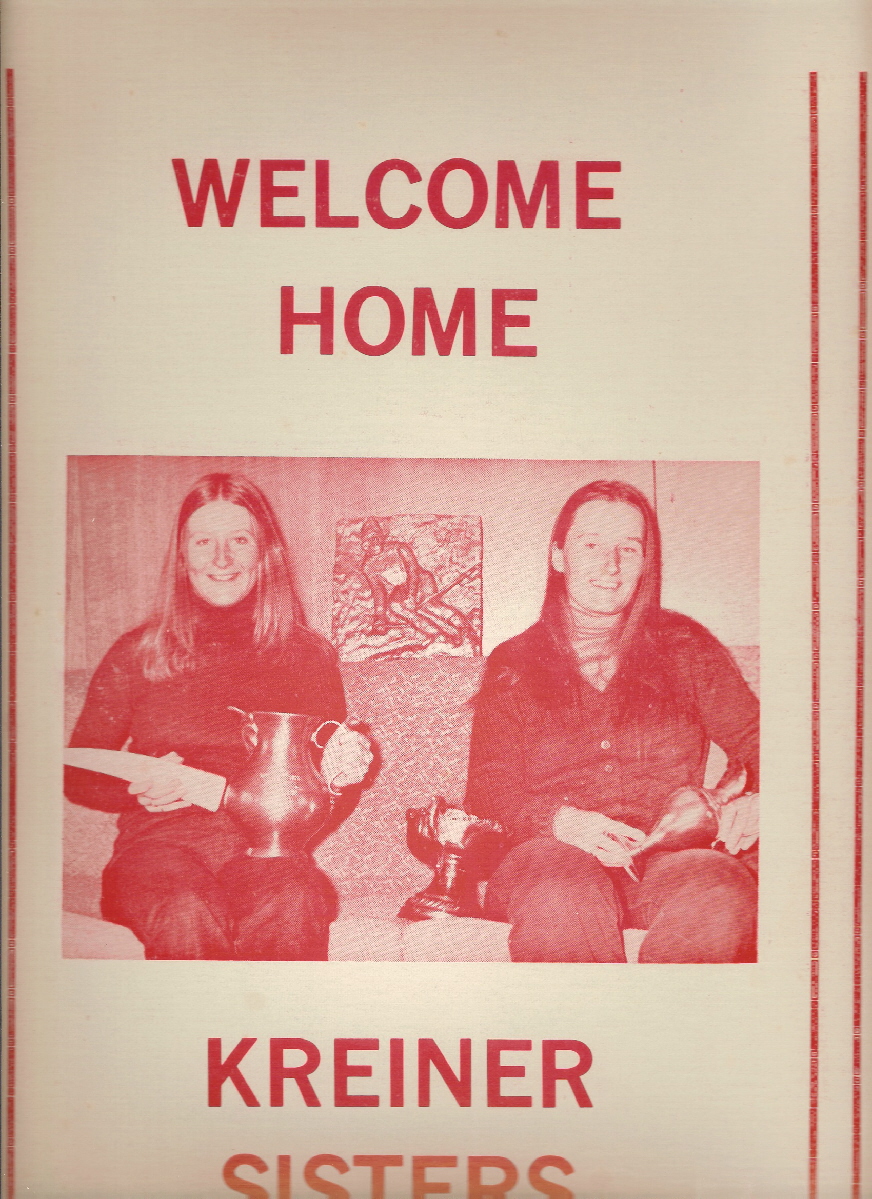

Back home in Timmins, Hal and Peggy Kreiner were unaware their youngest daughter had made ski racing history. “The phone woke my dad in the early morning,” Laurie says. “Someone heard of Kathy’s win on the radio and called to tell him.” The “Kreiner Sisters” were brought home to Northern Ontario on Air Canada in first class; there was a huge celebration in the local arena. “One man,” Laurie says, “drove all the way from Niagara Falls to give us our own Hudson’s Bay coats.” It was a homecoming to remember.

Back Home in Timmins

The years that followed brought more skiing highs — and many lows — to the Kreiner family. Kathy continued to race after her gold medal win until retirement came in the 1980s and she moved into a career in sports psychology. Hal passed away in 1999; Peggy in 2011. By then their six children were scattered across Canada, working as authors, teachers, and business leaders.

As for Kamiskotia: “Two of our brothers on various gap years looked after the ski hill,” says Laurie, “then me, after I retired from ski racing. For 19 years I kept the family interest going while raising my family.”

Quad lifts, snowmaking, and a new chalet were added to the resort. But, says Laurie, running a ski area is “a tough business.” With the advent of Sunday shopping, online activities, and the cost of hydro, the Kreiners could no longer maintain it as a family-run business. Eventually, Kamiskotia became a non-profit enterprise for the city of Timmins.

For their dedication to the sport, the Kreiners paid a very dear price. Laurie’s oldest son lost his life hitting a tree in a ski racing accident. “Skiing has been really hard on my family,” she says. “Catastrophic, actually. But yes… I still do it. I like the feeling of the body after skiing. I like the fresh air. I like the peace and quiet.”

She adds: Our family is no longer actively involved in day-to-day, year-to-year activities of Kamiskotia, but I ski there with my memories, spirits in me, bringing a smile in my minds eye.”

All this thanks to Peggy and Hal “Cool Doc” Kreiner, and their dedication to making a mountain out of a Timmins molehill.